The Algorithm's Grip II: Navigating the Antitrust Tightrope in Silicon Valley

Some learnings from History, Financial Markets and Investor VC Backlash

Please see “The Algorithm’s Grip I: How Pricing Bots Could Undermine Fair Markets”, Part 1 of this series

The Algorithm's Grip: How Pricing Bots Could Undermine Fair Markets

In the increasingly digital landscape of modern commerce, algorithms have become ubiquitous, silently shaping the prices we pay for everything from groceries to plane tickets. These sophisticated software programs, often referred to as "pricing bots," are designed to

My exploration of the impact of algorithms on fair trade and consumer rights led me down a winding path, one that ultimately took me back to the very foundations of antitrust law. It started with the realization that these powerful lines of code, designed to optimize and personalize our digital experiences, could also be used to manipulate markets, stifle competition, and ultimately harm the very consumers they were meant to serve. This realization sparked a deeper dive into the world of antitrust, a journey that took me from the historical case of Standard Oil to the contemporary battlegrounds of Silicon Valley.

Standard Oil, the quintessential example of a 19th-century industrial monopoly, employed tactics like predatory pricing and exclusive dealing arrangements to crush its rivals and control entire markets. Fast forward to the digital age, and we find ourselves facing a new breed of behemoths—tech giants like Google, Amazon, and Facebook—whose dominance is fueled by sophisticated algorithms that determine what we see, what we buy, and even what we think.

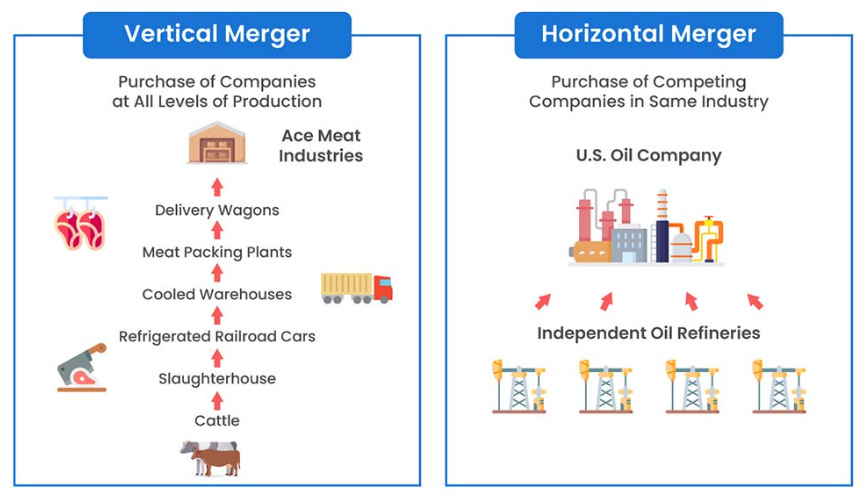

A lot changed in 2021, when the youngest ever FTC Chair was installed - Lina Khan. Reading Lina Khan's groundbreaking work on Amazon's Antitrust Paradox, I began to grasp the unique challenges posed by these platform-based businesses. Their ability to operate across multiple levels of the market, blurring the lines between commerce and infrastructure, demands a reevaluation of traditional antitrust frameworks. The very distinction between horizontal and vertical mergers, once a cornerstone of antitrust analysis, seems to blur in the face of these sprawling digital ecosystems.

I see parallels with the financial markets, where regulations like the Volcker Rule were put in place to prevent proprietary trading, market manipulation, and conflicts of interest among market makers (especially after 2008). These regulations, designed to ensure fairness and transparency in traditional markets, offer valuable insights against conflicts of interest, as we grapple with the complexities of algorithmic antitrust in the digital age.

This article attempts to synthesize the historical lessons of Standard Oil with the contemporary challenges posed by Silicon Valley's algorithmic power. It's a journey that has challenged my assumptions, broadened my understanding, and left me with a profound sense of urgency. The stakes are high, and the need for a nuanced, adaptable approach to antitrust enforcement has never been greater. The future of fair competition hangs in the balance, and the algorithms that impact most of our lives will ultimately determine whether we land on the side of innovation or exploitation.

Note: Mine is an overview that blends many facets of algorithms, history, learning lessons from financial markets, VCs and case studies furnished in the public domain. I am not a legal expert in any way or form. To drill deeper into the legal aspects please review this account by Matt Stoller, which is excellent:

Historical Context: Standard Oil and the Foundations of Antitrust

To truly grasp the complexities of algorithmic antitrust, it's essential to look back at the origins of antitrust law itself. The story of Standard Oil, a company that became synonymous with monopolistic practices in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, provides a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked market power.

John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, through a series of shrewd business maneuvers and ruthless tactics, came to dominate the oil industry. The company employed a range of anti-competitive practices, including:

Predatory Pricing: Standard Oil would slash prices in specific regions to drive competitors out of business, often operating at a loss in the short term to achieve long-term market dominance. Once rivals were eliminated, prices would inevitably rise.

Exclusive Dealing Arrangements: Standard Oil used its leverage to coerce railroads and other transportation providers into offering preferential rates and exclusive contracts, effectively shutting out competitors from essential distribution channels.

Vertical Integration: Standard Oil controlled nearly every aspect of the oil production process, from extraction and refining to transportation and distribution. This vertical integration gave the company an unparalleled advantage, making it difficult for competitors to gain a foothold in the market.

Public outcry against Standard Oil's monopolistic practices, fueled by investigative journalism like Ida Tarbell's exposé "The History of Standard Oil Company," led to the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. This landmark legislation, aimed at preventing monopolies and fostering competition, became the bedrock of modern antitrust law.

In 1911, the Supreme Court, in the case of Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, found Standard Oil in violation of the Sherman Act and ordered its breakup into separate companies. This landmark ruling established the "rule of reason," a principle that continues to guide antitrust enforcement today.

The legacy of Standard Oil serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us that unchecked market power, regardless of the industry or technology involved, can stifle innovation, harm consumers, and undermine the very foundations of a fair and competitive market economy.

The Algorithm's Ascent: Powering Silicon Valley's Dominance

Fast forward from the oil fields of Pennsylvania to the sun-drenched campuses of Silicon Valley, and we encounter a new breed of corporate titan, one whose power is derived not from control over physical resources but from mastery of algorithms and data. Companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook (now Meta), and Apple have risen to become global behemoths, shaping the very fabric of our digital lives.

At the heart of their dominance lies the algorithm, a ubiquitous force that drives virtually every aspect of their business models. These intricate lines of code determine:

What we see: Google's search algorithm ranks websites, shaping our access to information and influencing public discourse. Facebook's news feed algorithm curates the content we consume, shaping our perceptions and influencing our social interactions.

What we buy: Amazon's recommendation engine suggests products, subtly guiding our purchasing decisions. Apple's App Store ranking algorithms determine which apps gain visibility and reach, influencing the success of app developers.

How we target and are targeted: Google and Facebook's advertising algorithms enable businesses to reach specific demographics with laser-like precision, shaping consumer behavior and influencing market dynamics.

While these algorithms offer undeniable benefits in terms of efficiency, personalization, and convenience, they also raise concerns about their potential for anti-competitive behavior. Just as Standard Oil used its control over oil pipelines and transportation networks to stifle competition, these digital giants can leverage their algorithmic dominance to manipulate markets and maintain their grip on power.

Lina Khan, in her seminal article "Amazon's Antitrust Paradox," eloquently articulated the challenges posed by these platform-based businesses. The downloadable pdf is found here. She argued that their ability to operate across multiple levels of the market, acting as both a retailer and a marketplace provider, creates inherent conflicts of interest and opportunities for anti-competitive conduct. Amazon, for instance, can use its control over the platform to favor its own products over those of third-party sellers, giving it an unfair advantage and potentially harming competition.

The parallels between the market makers of Wall Street and these algorithmic titans are striking. Just as market makers can influence prices and liquidity in financial markets, these digital platforms can shape the flow of information, goods, and services in the digital economy. This raises crucial questions about the need for robust regulatory frameworks to prevent algorithmic manipulation and ensure a level playing field for all players.

Note: Other References on Lina Khan’s Writings can be found at Columbia Law’s site.

Algorithmic Antitrust Concerns: Echoes of Market Maker Practices, now Highly Regulated

To fully appreciate the potential for algorithms to distort competition, it's helpful to draw parallels with the world of financial markets. Market makers, specialized firms or individuals, play a critical role in providing liquidity and facilitating trading on exchanges. They essentially act as intermediaries, quoting bid and ask prices for securities, ensuring that there are always buyers and sellers available, and profiting from the spread between those prices. These spaces are typically highly regulated, with many “market makers” to ensure fair prices are quoted.

While market makers are essential for the smooth functioning of financial markets, their position of influence also creates opportunities for manipulation. If a market maker were to collude with others or abuse its position to distort prices or limit access to trading, it could undermine the integrity of the market and harm investors.

To prevent such scenarios, financial markets are subject to strict regulations, including a provision of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, commonly referred to as - the Volcker Rule, which was enacted in response to the 2008 financial crisis. The Volcker Rule prohibits banks from engaging in proprietary trading (trading for their own profit) and limits their investments in hedge funds and private equity funds. This regulation’s aim was - to prevent conflicts of interest and reduce the risk of banks using their market-making power to benefit their own trading desks at the expense of clients and the broader market. Exemptions were included (found in the attached document).

Now when you look at the Ad Exchange, you can see how powerful the “intermediary” role is. Google dominates search. In the example, this could look more like an “illiquid” market-making task. To mitigate risks, “Chinese walls” or “walled gardens” are typically drawn to ensure both sides remain independent. But you can guess the issue….some walls are easier to climb than others.

The parallels between market makers in finance and algorithmic platforms in the digital economy are compelling. Just as a dominant market maker could manipulate stock prices, a dominant tech platform could leverage its algorithms to:

Facilitate Price Fixing and Collusion: Imagine competing e-commerce platforms using algorithms to monitor each other's prices and automatically adjust their own to match or slightly undercut the competition. This could lead to a scenario where prices converge across the market, stifling price competition and harming consumers.

Engage in Market Power Abuse: A platform with a dominant market share could use its algorithms to engage in predatory pricing, setting prices below cost to drive out smaller competitors. Once the competition is eliminated, the platform could then raise prices, leaving consumers with fewer choices and higher costs.

Exploit Information Asymmetry and Opacity: The complexity and lack of transparency of many algorithms make it difficult for regulators and consumers to understand how prices are being set and whether anti-competitive practices are occurring. This opacity can create an uneven playing field, favoring the platform with the most sophisticated algorithms and access to data.

The challenges posed by algorithmic antitrust are amplified by the fact that digital platforms often operate across multiple levels of the market, blurring the lines between traditional categories like producers, distributors, and retailers. This makes it harder to apply existing antitrust frameworks, which were primarily designed to address issues in more clearly defined industries.

Horizontal and Vertical Mergers: A Shift in Antitrust Focus

Historically, the primary focus of antitrust enforcement has been on horizontal mergers, where companies operating at the same level of the market merge, reducing the number of direct competitors. For example, if two major airlines were to merge, it would raise concerns about reduced competition, potentially leading to higher airfares and less choice for consumers.

However, as Lina Khan has argued in her work, the rise of platform-based businesses necessitates a shift in focus to encompass vertical mergers as well. Vertical mergers involve companies operating at different stages of the supply chain or production process. While these mergers may not directly eliminate competitors, they can raise concerns if they give the merged company an unfair advantage over rivals or allow them to exert undue influence over suppliers or customers.

For example, if a dominant e-commerce platform were to acquire a leading logistics company, it could potentially give the platform an unfair advantage in shipping costs and delivery times, making it harder for competing retailers to compete. This is especially problematic in the context of digital platforms, which often operate across multiple levels of the market, blurring traditional boundaries between producers, distributors, and retailers.

Lina Khan's argument for closer scrutiny of vertical mergers, particularly in the tech industry, centers on the potential for these mergers to:

Foreclose Competition: A dominant platform could use a vertical merger to deny competitors access to essential inputs or distribution channels, effectively squeezing them out of the market.

Increase Barriers to Entry: Vertical mergers can make it more difficult for new entrants to gain a foothold in the market, as they may have to compete with a vertically integrated company that controls key aspects of the supply chain.

Facilitate Self-Preferencing: A platform could use a vertical merger to favor its own products or services over those of its competitors, giving it an unfair advantage and potentially harming consumers.

Recent antitrust cases highlight this shift in focus towards vertical mergers. Here are some notable examples:

Illumina and Grail (Vertical): The FTC challenged Illumina's acquisition of Grail, a cancer detection test maker that relies on Illumina's DNA sequencing technology. The concern was that Illumina, as a dominant provider of sequencing technology, could use the merger to raise prices or limit access to its technology for Grail's competitors, harming innovation in the emerging market for multi-cancer early detection tests.

Visa and Plaid (Vertical): The DOJ blocked Visa's acquisition of Plaid, a fintech startup that connects financial apps to users' bank accounts. The argument was that Visa, a giant in payment processing, was acquiring a potential competitor in the online debit market, as Plaid could have eventually developed its own payment processing system. The DOJ's action aimed to prevent Visa from stifling this potential competition and maintaining its dominant position.

Nvidia and Arm (Horizontal): While this was a horizontal merger, it's worth noting that the FTC's decision to block it also considered the potential vertical implications. Arm's chip designs are used in a wide range of devices, and the concern was that Nvidia, a dominant player in GPUs, could use its control over Arm to favor its own products, potentially harming competition in markets for data centers, self-driving cars, and other technologies.

The focus on vertical mergers reflects a recognition that traditional antitrust frameworks, primarily designed to address horizontal competition, may not be adequate to address the complexities of digital platforms and their ability to operate across multiple levels of the market. If you have 5 hours available, this is worth the watch.

Market Reactions: Silicon Valley's Discontent and the VC Backlash

The recent surge in antitrust actions against Big Tech has generated a chorus of mixed reactions, particularly among Silicon Valley Billionaires and the venture capital (VC) community that fuels its growth. While some applaud these efforts as a necessary correction to curb unchecked market power, others express deep concern about the potential chilling effect on innovation and investment.

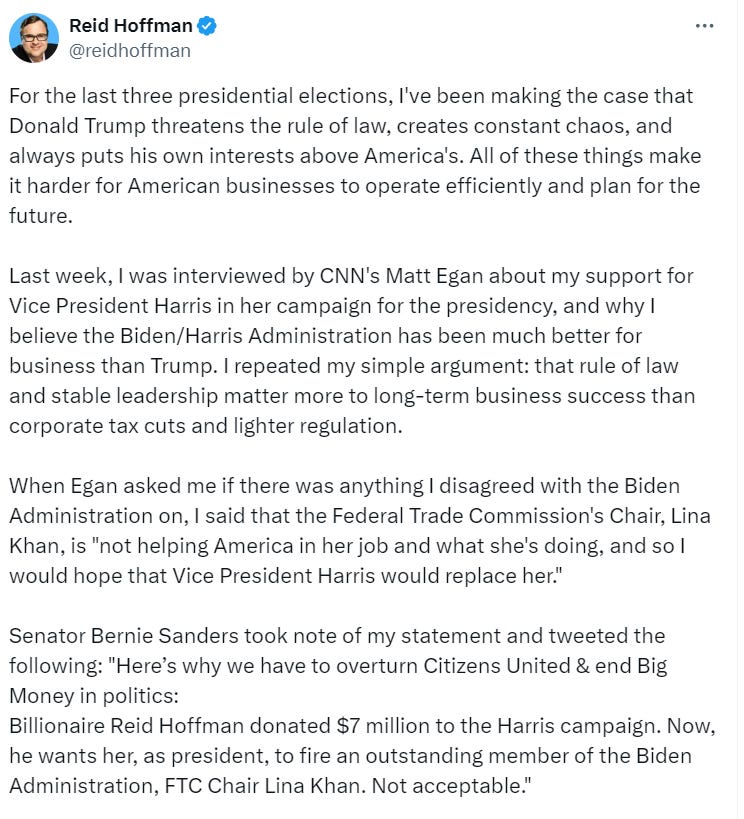

This is Reid Hoffman:

Another voice of dissent comes from Jason Calacanis, a well-known venture capitalist and angel investor. In a series of “Lina Khan has killed the M&A business” tweets, he vehemently criticized the aggressive approach of Lina Khan and the FTC, arguing that it is harming the VC ecosystem and stifling innovation. For useful and relevant terminology, please see this. His primary concerns revolve around the impact on mergers and acquisitions (M&A), a crucial exit strategy for VC-backed startups. I have heard it repeated, in different ways by various VC’s and Billionaires (including as acknowledged by Lina Khan at a recent conversation at Stanford (Minute 42 has a relevant question):

Relevant Screenshot:

Calacanis's perspective echoes a broader sentiment within segments of the tech industry and the investment community. They argue that:

Large tech companies are engines of innovation and economic growth. Breaking them up or subjecting them to heavy-handed regulation could stifle innovation, harm the overall economy, and ultimately hurt consumers.

The focus should be on demonstrable consumer harm, not just on company size or market share. They contend that antitrust enforcement should target practices that directly harm consumers, such as price fixing or the degradation of product quality, rather than simply seeking to reduce the size or influence of successful companies.

The current regulatory climate creates uncertainty and discourages investment. The fear of antitrust action could make investors hesitant to fund ambitious startups, particularly those that aim to disrupt existing markets or challenge established players.

The Weaponization of the FTC - U.S. House of Representatives Investigation Reports

Recent investigations on the FTC have been conducted by the House Committee, and speak to the many dissenting views on their actions, which in the interest of providing a balanced view are referenced herein. The 2 Reports are:

(1) The Weaponization of the FTC: An Agency's overreach to harass Elon Musk's Twitter (Mar 2023)

(2) The Weaponization of the FTC Part II: Harassment of Elon Musk (Oct 2024)

A copy of the pdf is available here

Beyond the VC Backlash:

However, the market reaction to the antitrust wave is far from monolithic. Many consumer advocates, academics, and policymakers see these actions as long overdue and necessary to address the growing power of tech giants. They argue that:

Dominant platforms have used their market power to stifle competition, harming both consumers and smaller businesses. They point to examples of platforms favoring their own products over those of competitors, using data to unfairly advantage themselves, and engaging in practices that make it difficult for rivals to emerge.

The focus on consumer harm is too narrow. They argue that antitrust law should also consider the broader impact of market concentration on innovation, economic opportunity, and even democracy.

Strong antitrust enforcement is needed to restore a level playing field and ensure a more dynamic and innovative digital economy. They believe that curbing the power of dominant platforms will ultimately benefit consumers by fostering greater choice, lower prices, and a more diverse marketplace of ideas.

A Path Forward Amidst Uncertainty:

The current antitrust debate has injected a level of uncertainty into the tech industry and the VC world that fuels its growth. The long-term consequences of this shift in regulatory focus remain to be seen. However, it's clear that finding a balance between fostering innovation and promoting competition will be crucial in shaping the future of the digital economy.

The Regulatory Tightrope: Balancing Competition and Innovation

The surge in antitrust scrutiny of Big Tech reflects a growing recognition that the digital landscape demands a more agile and adaptable approach to antitrust enforcement. Traditional frameworks often focused on narrow definitions of market share and demonstrable consumer harm, may struggle to capture the nuances of algorithmic power and its potential to distort competition in rapidly evolving digital markets.

Regulators around the world are grappling with these challenges, walking a tightrope between promoting innovation and curbing anti-competitive practices. Here's a look at some of the key regulatory actions and investigations:

Google (Search and Advertising): Google has been a frequent target of antitrust scrutiny, facing investigations and lawsuits on both sides of the Atlantic.

European Commission: The EU has fined Google billions of euros for a range of antitrust violations, including favoring its own comparison shopping service in search results, using its Android operating system to unfairly promote its own apps, and restricting advertisers from using competing platforms. Postnote: Google challenged the fine, and recently won.

US Department of Justice: The DOJ filed an antitrust lawsuit (which it won in Aug 2024) against Google, alleging that the company has illegally maintained its monopoly in search and search advertising through exclusionary agreements with phone manufacturers and web browsers, as well as by leveraging its dominance in search to favor its other products.

Amazon (E-commerce Marketplace): The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been investigating Amazon for potential antitrust violations related to its sprawling e-commerce empire. The focus of the investigation is twofold:

Self-Preferencing: The FTC is examining whether Amazon uses its control over the marketplace platform to favor its own products over those of third-party sellers, giving it an unfair advantage and potentially harming competition.

Exclusionary Conduct: The FTC is also looking into whether Amazon engages in practices that make it difficult for competing marketplaces to thrive, such as imposing restrictive terms on sellers or using its vast trove of data to unfairly advantage its own products.

FTC Files Suit Against Amazon (26/9/2023): Details found here

Details of FTC Suit: Here (172 Pages: Note The Algorithm and Project Nessie)

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs): While not a tech company, the scrutiny of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) like Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, and OptumRx illustrates how algorithmic power can distort competition in healthcare.

The Issue: PBMs use complex algorithms to determine which drugs are included in their formularies (lists of covered drugs) and at what cost-sharing levels. Concerns have been raised that these algorithms favor drugs that offer higher rebates to the PBMs, even if they are not the most clinically effective or cost-effective options for patients.

Regulatory Response: The FTC has launched an inquiry into the practices of PBMs, focusing on how their algorithms and rebate structures affect drug prices, competition, and consumer access to affordable medications.

Navigating the Challenges:

These cases highlight the complex challenges facing regulators as they attempt to apply traditional antitrust principles to the dynamic world of digital platforms. Some of the key challenges include:

Defining Relevant Markets: Determining the relevant market in the digital economy can be complex, as online platforms often operate across multiple industries and geographies.

Measuring Market Power: Traditional metrics of market power, such as market share, may not adequately capture the influence of digital platforms, which often exert power through their control over data, algorithms, and network effects.

Assessing Consumer Harm: While high prices are often a clear indicator of consumer harm in traditional antitrust cases, the harms caused by digital platforms can be more subtle and harder to quantify, such as reduced innovation, decreased privacy, or the erosion of consumer choice.

Finding a Path Forward: Fostering Fair Play in the Digital Age

The challenges posed by algorithmic antitrust demand innovative solutions that can keep pace with the rapid evolution of digital markets. Finding the right balance between fostering innovation and ensuring a level playing field for all participants is crucial for a healthy and dynamic digital economy.

Here are some potential solutions and policy recommendations that could help navigate the antitrust tightrope in the age of algorithms:

1. Increased Transparency and Explainability:

Algorithmic Audits: Independent audits of algorithms could help assess their potential for anti-competitive effects and ensure they are not designed to unfairly disadvantage competitors or manipulate consumers.

Data Access for Researchers: Providing researchers with access to anonymized data from platforms could enable them to study market dynamics, identify potential harms, and inform policy decisions.

Plain-Language Explanations: Platforms should be required to provide clear and concise explanations of how their algorithms work, in language that is understandable to both consumers and regulators.

2. Data Portability and Interoperability:

Empowering Consumers: Giving consumers greater control over their data and the ability to easily transfer it between platforms could reduce the power of data monopolies and foster greater competition.

Interoperability Standards: Establishing industry-wide standards for data sharing and interoperability could make it easier for new entrants to compete with established platforms and create a more interconnected digital ecosystem.

3. Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement:

Updating Legal Frameworks: Existing antitrust laws may need to be modernized to better address the unique challenges posed by digital markets, such as network effects, data-driven competition, and the potential for algorithmic collusion.

Increased Resources for Regulators: Antitrust agencies need to be adequately funded and staffed with experts who understand the complexities of the digital economy and can effectively investigate and prosecute antitrust violations.

Remedies That Address Algorithmic Harm: Antitrust remedies should go beyond traditional measures like fines and divestitures and explore innovative solutions that address the specific harms caused by algorithms, such as mandating changes to algorithmic design, promoting data sharing, or creating mechanisms for algorithmic accountability.

4. Promoting Ethical Algorithm Design:

Ethical Guidelines and Standards: Encouraging the development and adoption of ethical guidelines for algorithm design could help promote fairness, transparency, and accountability in the use of algorithms.

Algorithmic Impact Assessments: Requiring companies to conduct impact assessments before deploying algorithms with significant societal or economic impacts could help identify and mitigate potential harms.

Education and Training: Investing in education and training programs for engineers, data scientists, and other professionals involved in algorithm development could foster a deeper understanding of the ethical implications of their work.

A Collaborative Approach:

Finding the right path forward will require a collaborative effort involving businesses, regulators, academics, and civil society. Open dialogue, shared learning, and a commitment to fostering a fair and competitive digital landscape are essential for harnessing the benefits of innovation while mitigating the risks of algorithmic power.

Conclusion

The world of algorithmic antitrust has been a stark reminder that technological progress, while offering immense promise, also carries inherent risks. Just as the unchecked power of Standard Oil in the oil fields of Pennsylvania once threatened the foundations of a fair market economy, the algorithmic dominance of Silicon Valley's tech giants poses a similar challenge in the digital age.

The algorithms that power our digital lives, while often invisible to the naked eye, exert a profound influence on our access to information, our choices as consumers, and the very structure of our markets. Their potential for manipulation, whether intentional or unintentional, is undeniable. The parallels with the practices of market makers in financial markets, and the regulatory frameworks designed to curb their excesses, offer valuable lessons as we grapple with the complexities of algorithmic antitrust.

Recent antitrust actions against companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook, while met with mixed reactions, signal a growing recognition that the digital landscape demands a more agile and nuanced approach to antitrust enforcement. The traditional focus on horizontal mergers may no longer be sufficient in an era of platform-based businesses that operate across multiple levels of the market. Scrutiny of vertical mergers and algorithmic practices, as exemplified by the cases of Illumina and Grail, Visa and Plaid, and the investigations into PBMs, reflects this evolving understanding.

The path forward is not without its challenges. Defining relevant markets, measuring market power, and assessing consumer harm in the digital economy are complex endeavors. Yet, the stakes are too high to ignore. Finding the right balance between fostering innovation and protecting competition is crucial for ensuring a fair and dynamic digital marketplace.

Increased transparency, data portability, strengthened antitrust enforcement, and a focus on ethical algorithm design are essential components of a comprehensive approach. But ultimately, fostering a truly fair and competitive digital economy requires a collaborative effort involving businesses, regulators, academics, and civil society.

As we navigate the digital frontier, the algorithms we create will shape not only our markets but also our society. The choices we make today will determine whether the algorithm's grip leads to a future of concentrated power and stifled innovation or one of shared prosperity and boundless opportunity.

References

Historical Context:

"Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, 221 U.S. 1 (1911)." Link to Supreme Court decision

"The History of Standard Oil Company" by Ida Tarbell Link to book or relevant excerpts

Algorithmic Dominance and Antitrust Concerns:

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox" by Lina Khan (Yale Law Journal, 2017) Link to article

"The Separation of Platforms and Commerce" by Lina Khan (Columbia Law Review, 2019) Link to article

"The Volcker Rule: A Brief Summary" (Federal Reserve Board) Link to resource

"Artificial Intelligence & Collusion: When Computers Inhibit Competition" by Ezrachi and Stucke (Journal of Competition Law & Economics, 2015) Link to research paper

Horizontal and Vertical Mergers:

"FTC Challenges Illumina’s Proposed Acquisition of Cancer Detection Test Maker Grail" (FTC Press Release, 2021) Link to press release

"Justice Department Sues to Block Visa’s Acquisition of Plaid" (DOJ Press Release, 2021) Link to press release

"NVIDIA to Abandon Acquisition of Arm" (NVIDIA Press Release, 2022) Link to press release

Market Reactions and Venture Capital Perspectives:

Jason Calacanis's Twitter thread:

"Understanding TVPI, DPI, and IRR: Key Metrics for Informed Private Capital Investors" (BIP Ventures) Link to article

"The Antitrust Case Against Facebook Link to article

"The Wrath of Khan" (The Atlantic, 2024) Link to article

Regulatory Landscape and Policy Recommendations:

"European Commission - Antitrust: Commission fines Google €2.42 billion for abusing dominance as search engine by giving illegal advantage to own comparison shopping service" (2017). Google wins suit against fine (Sept 2024) Link to press release

"United States v. Google LLC" Link to DOJ lawsuit (won)

"FTC Sues to Block Microsoft Corp.’s Acquisition of Activision Blizzard, Inc." (FTC Press Release, 2022) Link to press release

"FTC Issues Policy Statement Regarding Rebates and Fees Paid by Drug Manufacturers to Pharmacy Benefit Managers and Other Entities in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain" (FTC Press Release, 2022) Link to press release

"Algorithmic Accountability: A Primer" ( 2018) Link to resource

"Competition Policy for the Digital Era" (OECD, 2019) Link to report

YouTube Related Videos Worth Watching (State of VC exits, M&A, IPOs etc) @Sept 24:

Great read! You coalesced many ideas into such a simple, readable framework with what I'm assuming is insider knowledge that someone like me would never have access too. The buy/sell graphic with %ad market share and the checklist at the end. Well done! Thank you for doing this.